A deep-dive analysis of the energy performance and efficiency of public buildings in England and Wales – undertaken by dedicated internet access providers Neos Networks.

The energy performance of public buildings in the UK can have a huge impact on our environment and the public funds that go into powering them. Some 40% of the UK’s annual energy use comes from buildings, which are also responsible for around one-third of the country’s greenhouse gas emissions. Buildings have been cited by the Committee on Climate Change (CCC) as a key challenge on the way to meeting net-zero targets.

To address the impact from the public sector, the UK’s Heat and Buildings Strategy and Public Sector Decarbonisation Scheme aims to cut emissions from public buildings by 75% – compared to 2017 levels – by 2037. So where is this target within reach, and which local authorities and public sectors face a greater challenge to meet it?

As experts in public sector network connectivity, we wanted to outline the size of the task to meet these standards and improve public building stock – and how better connectivity, smart tech and big data can drive the first steps. Our research analysed the Display Energy Certificate (DEC) of 450,074 public buildings in England and Wales, publicly available from the Department for Levelling Up, Housing & Communities, to investigate the energy performance of the UK’s public sector buildings. The metrics analysed included:

- DEC rating band

- A scale that runs from ‘A+’ to ‘G’, with ‘A+’ being the most efficient and ‘G’ being the least efficient

- DEC operational rating

- CO2 emission kg per m2 per year

- DEC CO2 tonnes output per energy source

- Electric rating (annual CO2 tonnes)

- Heating rating (annual CO2 tonnes)

- Renewable (estimated equivalent annual CO2 tonnes)

Full definitions, methodology and sources are available at the bottom of the report

In parts of this report, the DEC rating – which details the actual energy performance of buildings over the previous 12 months – has been compared with Minimum Energy Efficiency Standards (MEES) targets for non-domestic properties, which outline the ideal standard for domestic and non-domestic properties in the UK. Currently, the minimum energy performance certificate (EPC) requirement is an E. The 2030 target for non-domestic buildings is a B.

This report also details the scale of the opportunity for improving energy efficiency in public buildings, and explores the solutions for meeting public sector emissions targets.

Key report findings

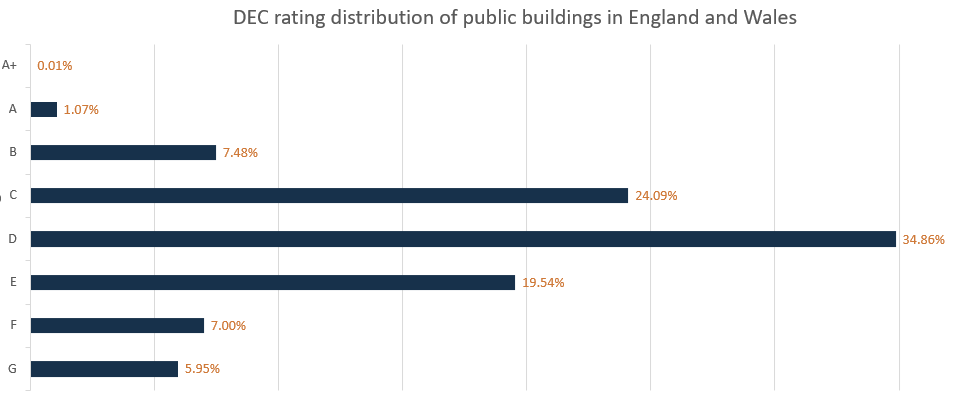

- Only 0.01% (just 48) public buildings scored the highest DEC rating of A+ in the UK, out of the 450,074 assessed in the available data

- 12.95% of public buildings fall below the current minimum energy efficiency standards (MEES) EPC rating of E for non-domestic buildings, based on their latest Display Energy Certificate score

- Just 8.57% of public buildings meet the MEES requirement target for 2030, which is a B rating

- 9 out of 10 (91%) public buildings will need upgrading in the next seven years to meet net-zero targets

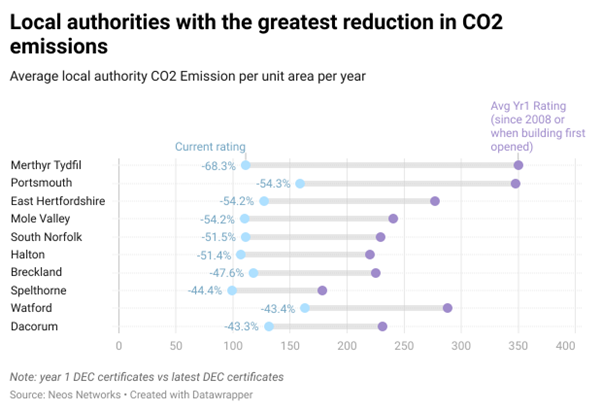

- Taking an average of all the public buildings in local authority areas across England and Wales, the operational rating (CO2 emissions per unit area per year) have fallen by 9.3% on average over the last 15 years, including buildings opened since

- To meet the government’s 2017 decarbonisation target of a 75% reduction, it would take 121 years at the current rate

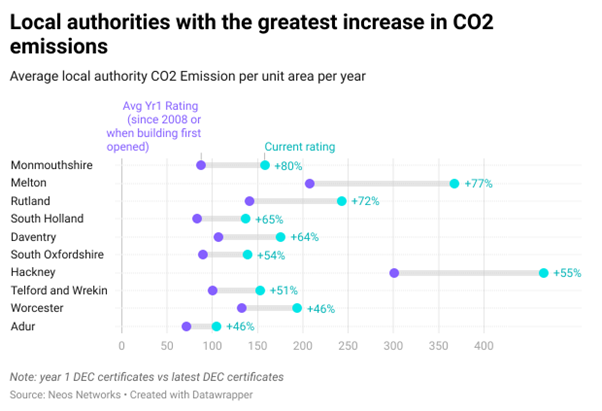

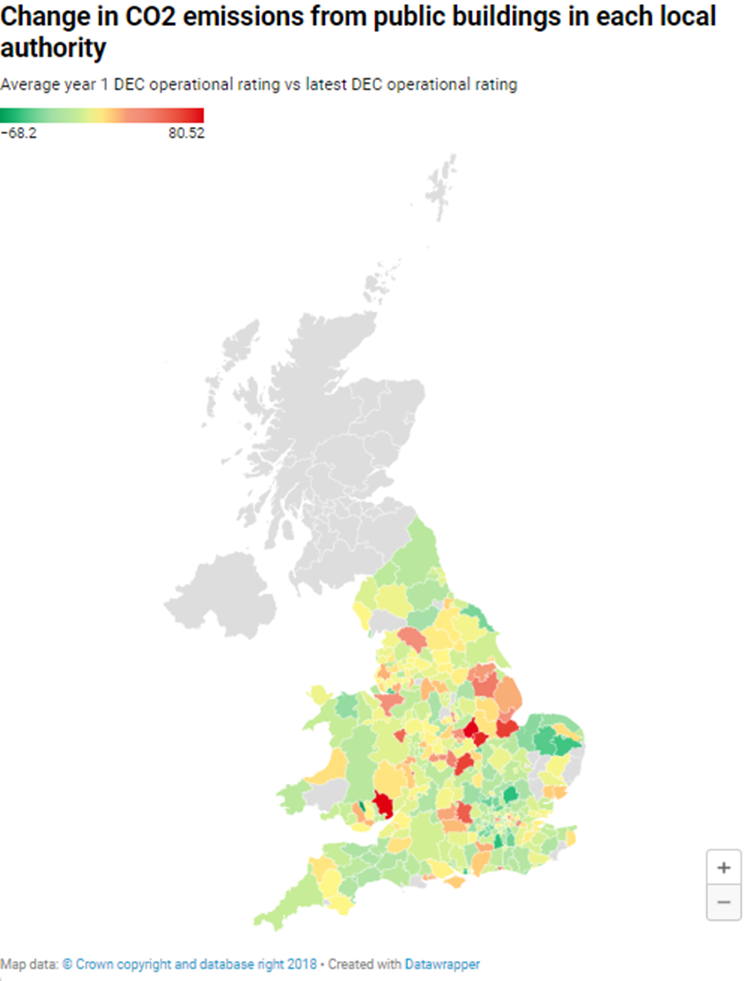

- CO2 emissions from public buildings have increased in almost a third (32%) of authorities, whereas 68% of local authorities have improved the energy efficiency of their public building stock

- London performs badly on several counts: total emissions, emissions per unit area per year and renewable energy use

- 20 (77%) of the 26 authorities with the lowest average ratings were in London

- One in seven (14%) NHS buildings are operating at ‘G’, the lowest DEC rating, more than any other public sector category in the dataset

- Leisure facilities are the highest operational rating CO2 emitters of all public buildings

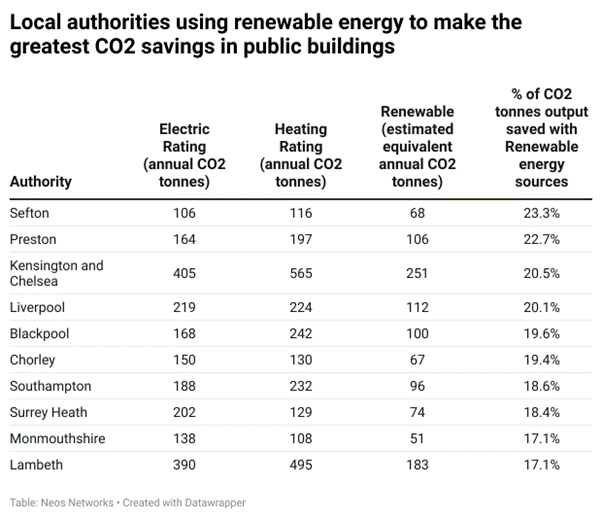

- Using renewable energy, Sefton local authority reduced CO2 output per square metre by 23% – more than anywhere else in England or Wales

Nationwide — the general picture

What challenge does the public sector face in improving the energy performance of public buildings?

More than ever, local authorities in England and Wales are having to prioritise where funding is spent. Between 2010–11 and 2020–21, central government funding for local authorities fell by over 50% in real terms, according to government data.

So, where does this underfunding leave our public buildings? What does the data tell us?

- The median DEC band for public buildings is D

- Over half (58%) of buildings are rated C or D

- There are just 48 public buildings rated A+

- 13% are rated F or G, below the current Minimum Energy Efficiency Standards of E

- Less than 9% meet the minimum energy efficiency standard requirement planned for 2030 — from A+ to B

- 91% of public buildings require upgrading to meet the 2030 target of a B EPC rating

What do DEC bands say about energy efficiency investment in England and Wales?

The government has set aside £2.5 billion for upgrading public buildings such as schools and hospitals. And the creation of the Department for Energy Security and Net Zero suggests that the government will really push to meet its targets. But some local authorities are facing a greater challenge than others in updating the energy efficiency of their public building stock.

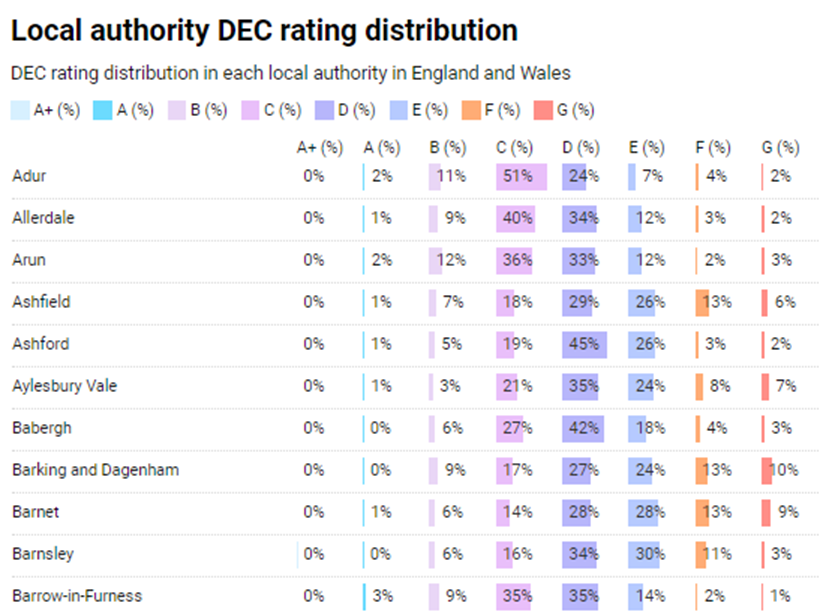

The areas with the highest proportion of A or A+ rated buildings are:

- West Northamptonshire: 13%

- Swindon: 12%

- Uttlesford: 9%

- Sevenoaks: 7%

- North-east Derbyshire: 4%

Only 2% (7 from 339) of local authorities can boast buildings with an average rating of C or above. Four of these are in Wales. They are:

- Vale of Glamorgan

- County of Gwynedd

- Flintshire

- Ceredigion

- Herefordshire

- Malvern Hills

- Adur

Some 20 (77%) of the 26 authorities with the lowest average ratings were in London. 77% of the authorities with an E rating can be found in the capital. Buildings in this band only just meet the minimum energy efficiency standard for non-domestic buildings. This all means that London will require significant investment to upgrade its buildings.

Reducing CO2 emissions: where should investment be concentrated?

Technology has improved greatly over the last 10-20 years, giving rise to new materials, construction methods and smart devices to improve the energy efficiency of a building. For smart devices to function, however, local authorities first need a solid foundation of connectivity. Networks will, therefore, need to be a primary focus of investment.

Public buildings measured with DEC ratings include those constructed before modern, energy efficient construction methods. According to the UK Green Building Council, 80% of all the buildings that will exist in 2050 have already been built. Some local authorities across England and Wales will have to contend with buildings that are centuries old — and retrofitting much of the existing building stock.

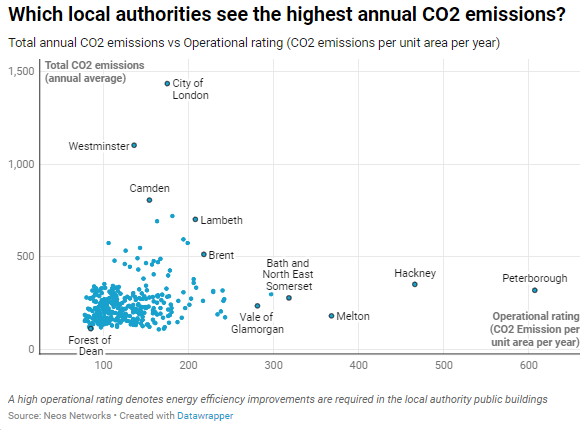

Total CO2 emissions per local authority

Measuring the cumulative emissions from public buildings in each council area, 9 of the top 10 CO2 emitters are in London. The City of London emits the greatest amount of CO2 per year on average, followed by the boroughs of Westminster, Camden, Kensington & Chelsea, and Lambeth. Of course, as places within the capital, these areas are home to more – and often bigger – public buildings than many parts of England and Wales.

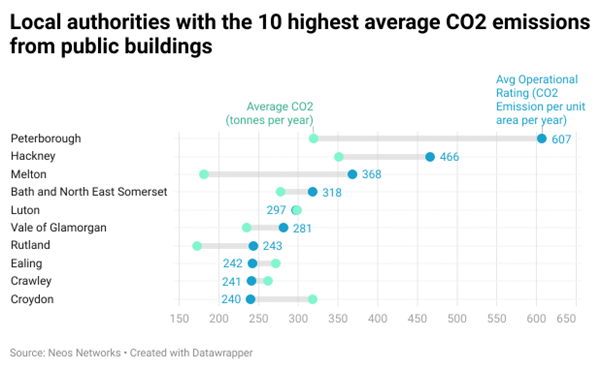

Operational rating average CO2 emissions per local authority

We can gain a more accurate picture of where investment is required by looking at annual CO2 emissions kg per m2. This gives us the operational rating for public buildings in each local authority. From that we can calculate the average for the area.

Examining CO2 emissions kg per m2, Peterborough is revealed to be the biggest polluter – and the local authority most in need of investment for upgrading public buildings.

Its operational rating of 607 kg of CO2 per m2 per year is more than six times higher than some authorities. Even Hackney, in second place on the list, emits almost a quarter less CO2. Fifth-placed Luton emits half the amount of CO2 that Peterborough is responsible for.

At the other end of the scale, West Devon and Buckinghamshire councils do the least polluting. They both emit 78 kg CO2 emissions kg per m2 – just 13% of Peterborough’s emissions.

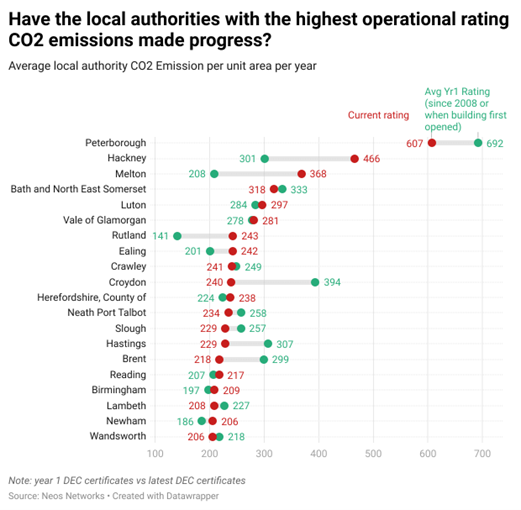

Is action already being taken?

Using historical data, we can see whether local authorities have been making progress in reducing the operational rating of their public building stock. This data compared the average operational ratings of public buildings in each area, to the average year 1 operational rating first taken for each building.

Nationwide — change over time

Have England and Wales experienced overall improvements in energy efficiency? And how does connectivity play a part?

Using England and Wales’ historical DEC database in the same way as the end of the previous section, we can take a nationwide view of the change in the CO2 emissions of public buildings since DEC ratings were introduced in 2008. This compares the current operational rating (annual CO2 emissions per m2 in kg) of buildings in the database to their first/earliest recorded operational rating.

Using this method, we can see that operational rating CO2 emissions from public buildings have fallen by 9.3%, on average, in the last 15 years.*

*Calculated from the sum CO2 output from each local authority in England and Wales, taking into account buildings that have been constructed since.

To achieve the Public Sector Decarbonisation Scheme core 2037 goal, the government would need a 3.75% annual reduction in operational ratings of public buildings.

We find that based on current trends, the CO2 emission per m2 is reducing by just 0.62% annually.

To meet the government’s 2017 target of a 75% reduction, it would take 121 years at this current rate. If things continue in this way, England and Wales won’t achieve Public Sector Decarbonisation Scheme goals until the year 2138.

Government will have to act to provide local authorities with the funding to make real progress. As smart technology becomes used more widely and AI-sourced data highlights more opportunities for efficiency, the pace of change should pick up. Of course, local authorities will first need to invest in the network solutions required by such innovations.

The role connectivity plays in improving energy efficiency

Smart technology has become increasingly common in UK homes and building management. Its increased use means more data insights to inform actions, on both the consumer side and for energy providers. Which elements can the public sector benefit from?

The “internet of energy (IoE)”*

Building Internet of Things (IoT) tech into the national grid will reduce wastage and make energy use more efficient. Energy providers can balance energy demand and consumers – such as local authorities – can use appliances when it costs less.

Machine learning and big data in the built environment**

According to the UN’s 2017 Global Status Report, active controls could save up to 230 EJ cumulatively to 2040 – around twice the energy consumed by the world’s buildings in a year. The UK government estimates that savings from a digitalised, flexible energy system could be worth £30-70bn – between now and 2050.

To achieve this, smart meters and smart building systems are collecting more and more data, supporting the AI and machine learning (ML) behind building control systems. Devices learn occupant heating/ cooling preferences and schedules, and also respond to external weather conditions. So a school, for example, might be heated more during a cold snap, but only on weekdays.

Data network connectivity

The majority of councils currently run smart buildings and networks in silos. But collecting and sharing energy data across a network of public buildings will mean other teams and neighbouring local authorities can make better energy decisions. Nearby buildings might even be linked or share heat recovery.

Read more about the relationship between connectivity and energy efficiency.

“Local government is already at the forefront of the fight against climate change, but it can be challenging to stay on top of the emerging obligations and opportunities…Barriers include a lack of inter-departmental and stakeholder coordination, lack of access to affordable and readily available energy efficiency technologies, and limited capacity and experience, which prevents many local authorities from gathering sufficient information about their energy performance.“

Which areas are winning the energy efficiency race?

Our research shows that 68% of local authorities have improved the energy efficiency of their public building stock – by reducing the average CO2 emission per unit area per year.

With 68% of authorities showing improvement, that does mean that CO2 emissions from public buildings have increased in almost a third (32%) of authorities. The five authorities where emissions have risen most are:

Where do London’s local authorities stand?

London authorities ranked, on average, among the worst performing for operational rating CO2 emissions. But has the capital reduced its CO2 output in the last 15 years?

Twenty-two out of 32 London boroughs have cut their level of emissions. On average, Greater London’s public buildings have reduced their CO2 emissions by just under 5%.

Croydon was the top performing authority in London, reducing its emissions by 39%. Hammersmith and Fulham came next, with a reduction of 34%, followed by the City of London with a reduction of on -27%.

At the other end of the scale, CO2 output from Hackney’s public buildings shot up by 55%. Bexley increased its emissions by 37% and Ealing’s rose by a fifth (20%).

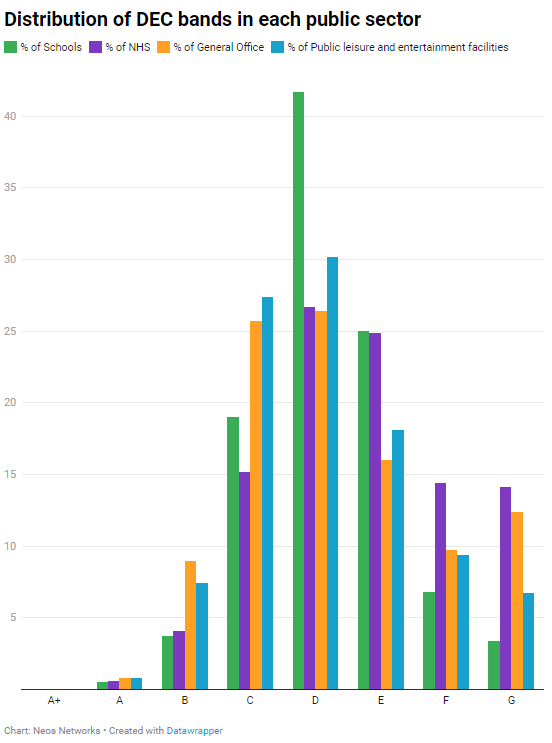

Are some public sectors more energy efficient than others?

By analysing differences in data between four types of public building, we establish which sectors are most energy efficient – and where the greatest opportunities to improve lie. The four types of building are:

- Schools

- NHS buildings

- General offices

- Public leisure and entertainment facilities

According to the figures, 87% of public buildings in the UK meet the current minimum energy efficiency requirements. This leaves 13% of public buildings which fall below the minimum EPC rating of E, based upon their latest display energy efficiency scores.

As part of net-zero decarbonisation plans, the government MEES target for 2030 is for non-domestic buildings to fall within or above energy performance band B. Only 8.57% of public buildings in England and Wales are currently in this band.

Consequently, more than 9 out 10 (91.43%) will need to be upgraded in the next seven years. When we look at public buildings by function, we can see the scale of investment required by each sector.

Schools and education

Nine out of 10 (90%) schools in England and Wales meet the current minimum energy efficiency requirements (an E rating). However, just 4% have achieved a B rating, which is the 2030 target.

NHS buildings

Currently, almost three-quarters satisfy the minimum energy efficiency requirements, but just 5% will in 2030.

General office buildings

More than three-quarters (78%) hit current targets, yet only 9% would be energy efficient enough in 2030.

Public leisure and entertainment facilities

84% meet current requirements, but just 8% are ready for 2030 targets.

Sector by sector in depth

Schools and education

Some three-quarters (75%) of schools in England and Wales have an DEC rating of D or below – lower than the nationwide average.

They do have the lowest operational rating (CO2 emissions per unit per year) among public buildings, and their emissions have fallen by 10%, on average, over the last 15 years. But other public building sectors have all seen their CO2 output drop by more in that time.

NHS buildings

Four in five (80%) NHS buildings are rated D or below for their energy performance, with 14% working at the lowest DEC rating, which is G.

This situation is exacerbated by the slow pace at which new hospitals are being built. Despite the government’s 2019 manifesto promise of 40 new hospitals, only 10 had been granted planning permission by February 2023.

Operational ratings for NHS buildings have dropped by 16% in the last 15 years, which is nearly double the average of a 9% reduction in emissions. Half of this 16% fall is due to using renewable energy – the biggest difference renewables have made to any public sector.

This highlights NHS facilities’ potential for improvement when money is invested wisely.

General offices

More than any other category of public building, general office spaces have the highest proportion of buildings rated B or above – nearly double the rate of schools or NHS buildings. These buildings are already meeting the government target for 2030.

General offices have also experienced the greatest reduction in operational rating (CO2 emissions per unit area per year), with a 26% fall in CO2 emissions compared to year 1 DEC ratings.

Public leisure and entertainment facilities

Buildings in this category are the highest CO2 emitters per unit per year of all public buildings – even though their operational rating has dropped by 10%. The sector is also above the national average for reducing CO2 output through the use of renewable energy.

This ability of public leisure and entertainment facilities to put renewables to good use could help them to survive. In October 2022, ukactive (a leisure centre and gym association) surveyed their members about the effects of the energy crisis on the industry. The results showed that two-fifths (40%) of council areas are at risk of losing their leisure centre(s) or having reduced leisure services. Even more (74%) were classed as ‘insecure’, meaning a risk of closures or reduced services before April 2024.

With some investment in the underlying connectivity required, the public leisure and entertainment sector can harness the potential of smart tech and big data to direct a new focus on renewable energy. Then these buildings can reap even greater savings and safeguard their futures.

Future-facing solutions: how can 2037 targets be met?

By 2037, the government wants to reduce public sector building emissions by 75%. This is part of its Public Sector Decarbonisation Scheme. In addition, the Future Buildings Standard consultation proposed a tightening of Minimum Energy Efficiency Standards (MEES). And creating the new Department for Energy Security and Net Zero should put more weight behind energy efficiency initiatives.

To aid the public sector in reaching that 75% emission reduction target, phase 3 of the Public Sector Decarbonisation Scheme will provide £1.425 billion of grant funding over the 2022-2023 to 2024-2025 financial years.

As well as investing in renewable energy infrastructure, the sector might also consider underpinning renewable energy systems with smart technology and data sharing tech. If, for example, there was data sharing between local authorities and sectors in local areas, they could better share their learnings on energy efficiency.

Renewable energy: where it’s already being used to reduce CO2 emissions

While modern construction methods and retro-fitting public buildings are two popular ways to reduce carbon emissions, renewable energy can also have a huge impact.

In England and Wales, renewable energy is currently driving an overall reduction of 4.5% in CO2 emissions. However, some areas are doing better than others.

Sefton local authority is leading the way in England and Wales for using renewable energy to cut emissions from public buildings. Through renewable energy, the council in Sefton has actively reduced CO2 output per square metre by almost a quarter (23%). In fact, this figure is over five times (418%) higher than the average for local authorities in England and Wales, which currently stands at 4.5%.

Other local authorities making significant emissions cuts through renewable energy include Preston (23%), Kensington and Chelsea (21%), Liverpool (20%) and Blackpool (20%).

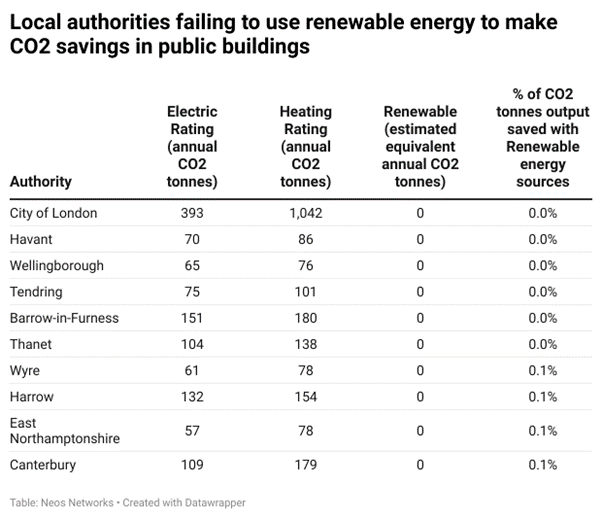

Which areas are not making cuts through renewable energy?

For some other local authorities, using renewable energy in public buildings remains an area of great potential.

According to the data, the City of London local authority has the most ground to make up. Despite ranking as one of the major CO2 emitters from public buildings in England and Wales in this report, it fails to source any of its energy from renewable sources to reduce this impact.

In addition to London, five other authorities failed to cut any emissions by using renewable energy. They are Havant, Wellingborough, Tendring, Barrow-in-Furness and Thanet.

With local authority budgets sometimes being too stretched for even basic services, more government funding is needed. Then councils can invest in renewable energy, retro-fitting and smart energy saving measures for public buildings: to meet net-zero emission targets.

Conclusion

As the public sector works to upgrade the energy efficiency of public building stock across England and Wales, our report highlights the extent of the challenge facing local authorities. They’re having to prioritise where funding is spent more than ever: central government funding for local authorities fell by 50% in real terms between 2010–11 and 2020–21.

Getting public building stock to a place where 2030 and 2037 targets look realistic will require a multi-faceted approach. There is great potential for innovations – like big data and smart technology – to play a key role in this approach, alongside renewable energy.

Glaring disparities between areas (and even neighbouring authorities) in energy performance and emissions control highlight the need for more collaboration. Widespread data sharing – underpinned by robust connectivity – can help to achieve this collaboration. When more investment is discussed, all parties should bear this in mind.

Definitions

- Display energy certificate (DEC) — the actual energy performance of a building, based on the previous 12 months

- Energy performance certificate (EPC) — the theoretical efficiency of a building

- Minimum Energy Efficiency Standard (MEES) / Non-domestic private rented property minimum standard — government legislation setting minimum energy efficiency requirements for non-domestic properties in England and Wales

- “Non-domestic buildings” — the category in government regulations which covers public buildings in the UK

Methodology & information

- Our research analysed 450,074 public buildings in England and Wales

- Method of analysis — the metrics used in this report to analyse the energy performance of the UK’s public sector buildings are:

- DEC rating band

- a scale that runs from ‘A’ to ‘G’, with ‘A’ being the most efficient and ‘G’ being the least efficient

- Operational rating

- CO2 emission kg per m2 per year

- CO2 tonnes output per energy source

- Electric rating (annual CO2 tonnes)

- Heating rating (annual CO2 tonnes)

- Renewable (estimated equivalent annual CO2 tonnes)

- DEC rating band

The DEC rating, which details the actual energy performance of buildings has, in parts of this report, been compared with Minimum Energy Efficiency Standards (MEES) targets for non-domestic properties, which outline the ideal standard

Sources

- Data for public building Display Energy Certificate (DEC) records obtained from The Energy Performance of Buildings Register — https://epc.opendatacommunities.org/

- DEC data includes certificates issued up to and including 29 Sep 2022

- Buildings that need a DEC certificate, as per definitions, here: https://www.gov.uk/check-energy-performance-public-building. Public authorities must have a DEC for a building if all the following are true:

- it’s at least partially occupied by a public authority (e.g. council, leisure centre, college, NHS trust)

- it has a total floor area of over 250 square metres

- it’s frequently visited by the public

- The analysis covers England and Wales. Data for Scotland and Northern Ireland was not included in the dataset supplied on the government website

- Note: the Isles of Scilly and Carmarthenshire are not found in the analysis due to incomplete datasets

- Heat and buildings strategy — https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/heat-and-buildings-strategy

- Public Sector Decarbonisation Scheme — https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/public-sector-decarbonisation-scheme

* https://neosnetworks.com/resources/blog/the-importance-of-connectivity-in-serving-an-energy-efficient-future/

**https://www.ucl.ac.uk/bartlett/news/2021/aug/smart-energy-smart-buildings-smart-health

Click here to expand chart

Click here to expand chart